- A-Z

- KONU DİZİNİ

- Cogito

- Çizgi Roman

- Delta

- Doğan Kardeş

- Ansiklopedi

- Bilim

- Çocuk Çizgi Roman

- Deneme

- Destan

- Dünya Klasikleri

- Efsane

- Eğitim

- Etkinlik

- Gençlik

- Gezi

- Hikâye-Öykü

- İlkgençlik

- Klasik Dünya Masalları

- Masal

- Mitoloji

- Modern Dünya Klasikleri

- Okul Çağı

- Okul Öncesi

- Oyun

- Resimli Öykü

- Resimli Roman

- Resimli ve Sesli

- Roman

- Romandan Seçmeler

- Röportaj

- Seçme Denemeler

- Seçme Öyküler

- Seçme Parçalar

- Seçme Röportajlar

- Seçme Şiirler

- Seçme Yazılar

- Şiir

- Edebiyat

- Anı

- Anlatı

- Biyografi

- Deneme

- Derleme

- Eleştiri

- Gezi

- Günce

- İnceleme

- Libretto

- Mektup

- Mitoloji

- Modern Klasikler

- Otobiyografi

- Oyun

- Öykü

- Polisiye-Gerilim

- Roman

- Senaryo

- Söyleşi

- Yaşantı

- Yazılar

- Genel Kültür

- Halk Edebiyatı

- Masal

- Kâzım Taşkent Klasik Yapıtlar

- Koleksiyon Kitapları

- Lezzet Kitapları

- Özel Dizi

- Sanat

- Kare Sanat

- Sergi Kitapları

- Şiir

- Türk Şiir

- Tarih

- XXI. Yüzyıl Kitapları

- Sosyoloji - Sağlık

- TEKRAR BASIMLAR

- YENİ ÇIKANLAR

- ÇOK SATANLAR

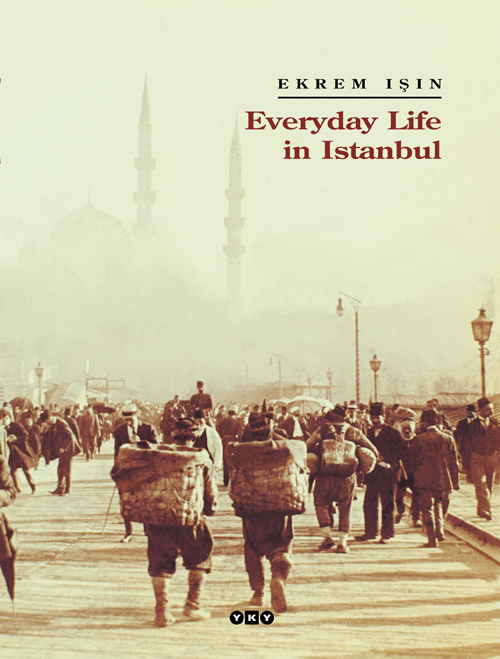

Everyday Life in Istanbul

-

Kategori:

Tarih -

Yazar:

Ekrem Işın -

Çeviren:

Virginia Taylor Saçlıoğlu -

ISBN:

978-975-08-0008-7 -

Sayfa Sayısı:

361 -

Ölçü:

22 x 29 cm -

YKY'de İlk Baskı Tarihi:

Eylül 1999 -

Tekrar Baskı Sayısı / Tarihi:

4. Baskı / Şubat 2018

Everyday life in istanbul is a collection of striking images along a journey back to the roots of the turk's social identity. A work embracing the history of an imperial city in a plane where man, culture and space relate to eachother, it is a noteworthy example of the new historiography, which sets up a balance among the social sciences. With its unique style and its theoretical framework set against a multidimensional background extending from politics to culture, from architecture to literature, it is at the same time a contemporary historian's gift to our city.

FOREWORD

Throughout history the pendulum of Istanbul’s everyday life has swung between the two opposite poles of the Ottoman world: mythos and utopia. This social oscillation, now heralding the end of the once golden ages that had come to a standstill, now accelerating the pace and opening up new horizons in human life, defined the city’s identity along the cultural fault line that divides Eastern mythos from Western utopia. Nourished by the empire’s rich geography, which was paired by fate with so many different cultures, this identity engraved Istanbul’s mark on the log of world civilization.

For Istanbul the mythos is an historical depth and a human experience with roots reaching far back into the past. As in empires all over the earth, in Istanbul as well this creative experience has taken shape within a fabric of cosmopolitan culture in which religion and race were interwoven. It remained the fundamental dynamic of everyday life for as long as the mythos was a protective law governing city life, a scale of values with their spiritual content in the public conscience, a touchstone for determining the ethical and aesthetic criteria of good and evil, the beautiful and the ugly.

The city’s mythos rose from the ashes of Rome. When this archaic worldview, based on military superiority and a sense of social security, was united with Constantine’s political utopia, the city’s star shone brightly throughout the medieval period. Byzantine Istanbul, which negotiated time’s labyrinth in a single millennium, reached the historical limits of self-sufficiency with its dazzling palace ceremonial, its interminable theological debates and its uprisings fomented by squalor and splendor. At the inevitable parting of ways, where enlightenment faded into twilight, the city’s legacy to the Ottomans was nothing more than the historical ruins of the destroyed mythos come crashing down now upon everyday life. Reviving Istanbul’s everyday life, the city’s new residents embraced the myth of empire, gleaming still beneath the ruins that they cleared away, and made it their own. And Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror went down in history not only as conqueror of a city called Constantinople but as conqueror of the Istanbul mythos as well.

Ottoman Istanbul is a scintillating jewel in the treasure chest of the Turks’ social identity, an identity we are on the verge of losing today. As much as the pirates who over the ages looted this treasure—a treasure we have buried now under a thick layer of neglect—the nameless heroes who measured its value in human life also permeated the atmosphere of this city. The Egyptian merchant who brought coffee from Alexandria to Tahtakale; the Uzbek dervish who stopped off on his pilgrimage to Mecca to first pay a visit to the mosque of Eyüb Sultan; the Armenian craftsman who transformed the Jewelry Bazaar into a radiant gleam of diamond, agate and emerald; the Jewish banker who discovered the magical power of money; the fire fighter who passed his youth on coffeehouse benches and cobbled pavements; the medrese scholar who mounted the staircase of knowledge rising to the rank of kadı; the Janissary colonel who left his head on the executioner’s block as a warning to others; and the Bektashi cloaked in the shadow of the şeriat sword—all of them together created the cultural climate that nourished and grew the Istanbul mythos until, in the end, mankind learned to co-exist in this environment.

Istanbul’s age of mythos experienced its first great upheaval in the 18th century. A welter of thoughts and emotions, harbingers of a utopia on the horizon of the future, affixed their own lifestyle to Istanbul’s identity in this century. From this time forward, a social specter with a split-personality would haunt the cultural atmosphere of everyday life, representing two diametrically opposed worlds. For those who had taken refuge in the secure world of the mythos, this specter was terrifying indeed. The utopia, strengthened under the aegis of political authority, was interfering in the life sphere of the mythos in such a way as to reinforce the collective fear, with the result that the home truths of everyday life were always weighed incorrectly in the balance of past values. Istanbul paid a high price for this miscalculation in 1730. As they destroyed the magnificent symbols of utopia at Sa’dabad, those who were eager now to salve the injured sense of justice in the public conscience undoubtedly fantasized about how they might recover the mythos’ lost paradise. But the paradisiacal gates had shut never to open again, and everyday life began to disintegrate on a city-wide scale. Henceforth the mythos would henceforth live its last days in the form of silent yet profoundly felt psycho-social upheavals in an Istanbul whose face was now obscured by darkness.

The 19th century is Istanbul’s utopian era. Casting its spell over the city, this magical power appeared on the scene in the guise of a “religion of civilization”, complete with its devout followers, crazed fanatics and zealous disciples bearing good tidings of paradise on earth to societal visions. Legends that Istanbul hung suspended in a place near to god on the summit of Mount Olympus sprang eternal in this religious community.

Utopia is a future concept that attempts to restructure the socio-cultural fabric of everyday life in Istanbul. Salvation from the grip of past time and from the mythos’ theme of purification from sin constituted the essence of this concept. This sense of liberation, which was transformed into a social construct during the 19th century, carved out a new Lebensraum for utopia by expunging past sins from the memory of everyday life. To this end, traditions are stashed away in storage chests and consigned to oblivion, and Istanbul eventually becomes the world’s biggest flea market as the dashed idols of the mythos pile up in the city’s marketplaces. While the world of traditional mentality, which finds no customers in this market, buries an entire social lifestyle in the depths of history, the now empty symbols of the mythos that has been left behind manage to survive today as touristic souvenirs in the nostalgia carnival.

As it carved itself a niche in Istanbul’s everyday life, utopia, creating no culture itself, functioned instead as a marketing mechanism for ready-made lifestyles manufactured in another time and place. Every debate that arose on the question of modernization therefore evolved into an advertising campaign to help rather than hinder the basic functioning of this mechanism. Eventually, the intellectuals, designing in the fertile soil of everyday life modernization projects to accord with the European visions of the great men of state, constructed a stage set for a world that could be imitated. In this fragile fantasy world man was transformed into an anxious creature who feels compelled to define himself in terms of another identity and is a perpetual cultural nomad in a life converted into a stage set. The highest price utopia exacted from Istanbul is, without doubt, that by destroying the mythos’ flexibility toward cultural norms it also destroyed the city’s knack of inventing a kaleidoscope of lifestyles, which had once been its principal feature. Indeed, the standardization of social responses, the caricature of life based on imitation at the individual level, and the city-wide proclamation by every new culture of its own hegemony without first being melted down in the imperial crucible, are the most glaring surviving vestiges of Istanbul’s torn fabric. Concomitantly, utopia gave Istanbul the idea of turning everyday life into a technical project. Steamboats and tram lines accelerated the pace of time, and city gas and electricity transformed traditional hardships into modern conveniences. In return however Istanbul paid for this with her very identity, which got lost somewhere between cultural alienation and the technical practicality of every life.

In its most general terms, everyday life is the history of the ordinary man. Every development that shapes the life of this anonymous hero falls within the domain of socio-historical research, whose purpose is detailed analysis of the dimensions of human-centered change to give a clear portrait of society. This approach, so out of favor with Turkey’s classical historiography, founded and developed on a political settling of scores with the past, has generally been the subject of the so-called popular genres of writing. Indeed, this popular genre, which from the 1920s became widespread among the literati in particular, has defined the contemporary perspective that views everyday life today as “Istanbul nostalgia”. Such popular writing about Istanbul by a group including authors and journalists such as Ahmed Rasim, Musahipzâde Celal, O. Cemal Kaygılı, E. Ekrem Talu, S. Muhtar Alus, and researchers such as A. Refik Altınay, R. Ekrem Koçu, R. Ahmed Sevengil and Haluk Y. Şehsuvaroğlu, has in a sense developed as a covert reaction against official historiography, bringing to the agenda the restoration of past time, in a sentimental and exaggerated style, as a counter to the harsh criticisms leveled at traditional Ottoman culture by Republican modernizers. The Istanbul image sculpted by these writers is the source of this “nostalgia literature”, which is mass-produced today and scarcely more than a pale imitation of its originators’ work.

The essays that constitute this book were written between 1985 and 1993 as the offshoots of a comprehensive study aimed at analyzing everyday life in Istanbul from a socio-historical standpoint. Part One has two primary themes: first, defining the social topography of Istanbul’s classical and modern periods from the point of view of everyday life and, second, laying bare the dynamics that shaped the city’s physiognomy. With this purpose in mind, a series of fundamental elements, extending from the neighborhood to the urban scale of life, have been treated in terms of their socio-cultural relations; the emphasis here is on the areas of life defined both by traditional institutions, which ensure historical integration, and by modern institutions, which cause disintegration. In Part Two, post-Tanzimat Istanbul is brought into the foreground and an effort is made to trace the social image of everyday life on the plane of human, cultural and spatial relations. A series of questions, such as the mode of operation of the social mechanisms that integrate human beings with everyday life, and the question of conformity, or the lack thereof, to the standard forms of life presented by the ideology of modernization constitute the basis for discussion in this section.

In sum, this work proposes to show that Istanbul is more than a mere fairground consisting of Beyoğlu and its entertainment culture and to offer an objective account of the history of this fantastic world, indeed of this vanishing social identity fraught with question marks, which nostalgia literature has turned into a fetish. The solution through scholarly investigation of the problems posed here would without doubt be the greatest reward this work could possibly receive.

?1995